Femcompetitor.com, grapplingstars.com, fciwomenswrestling.com, fcielitecompetitor.com, fciwomenswrestling2.com Christina-Morillo-pexel.com-photo-credit

November 9, 2021,

The goal posts continue to move in terms of defining freedom of speech.

Much now is considered out of bounds.

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction.

In today’s world, best wishes on that.

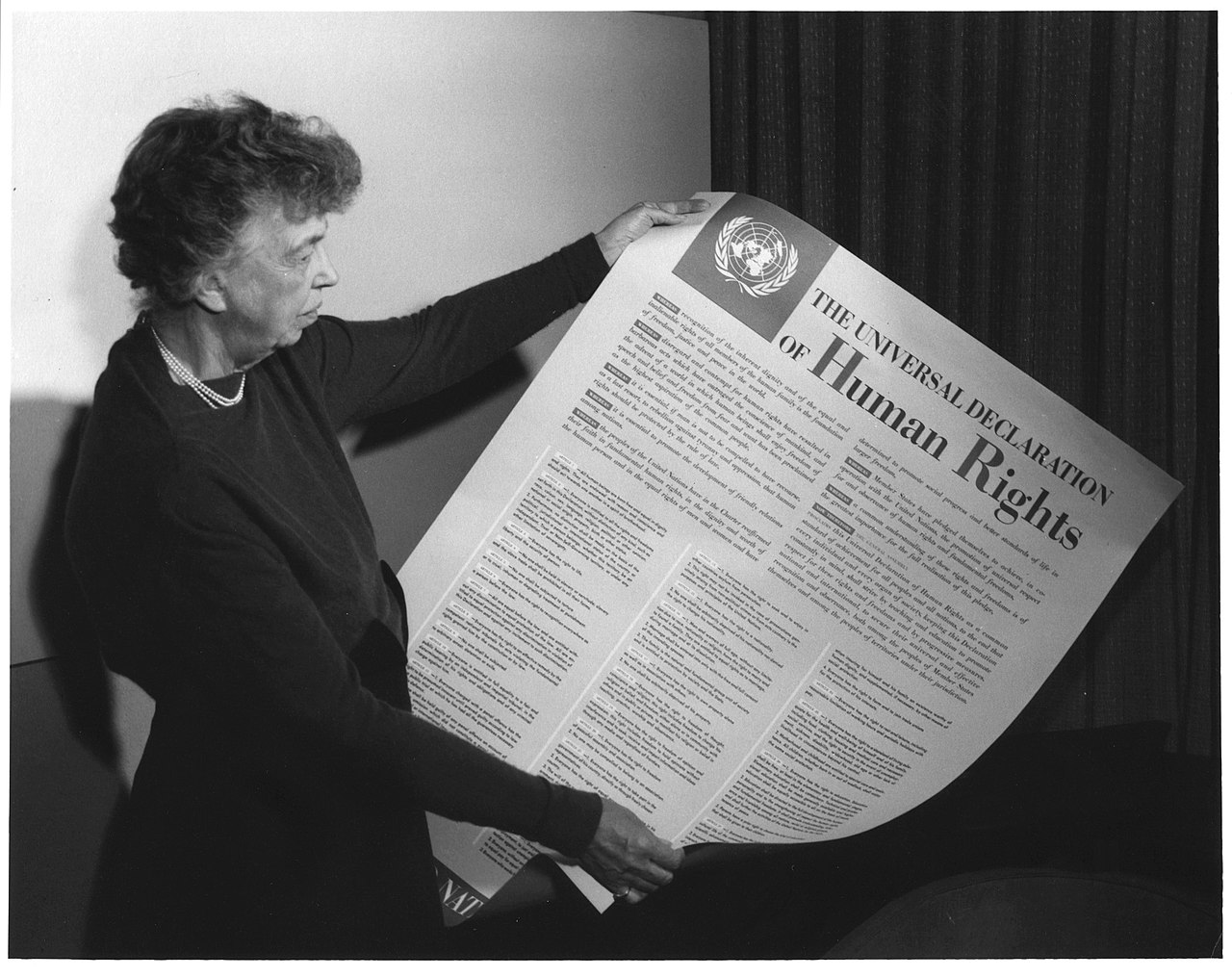

The right to freedom of expression has been recognized as a human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights law by the United Nations. A lot of countries have constitutional law that protects free speech.

Eleanor Roosevelt

In legal sense, the freedom of expression includes any activity of seeking, receiving, and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used.

Sounds good on paper.

But in reality?

Freedom of speech and expression, may not be recognized as being absolute, and common limitations or boundaries to freedom of speech relate to libel, slander, obscenity, pornography, sedition, incitement, fighting words, classified information, copyright violation, trade secrets, food labeling, non-disclosure agreements, the right to privacy, dignity, the right to be forgotten, public security, and perjury.

That basically defines speech in a public forum.

It is the private forum that has some concerned that people are less inclined to voice their opinions, even privately for fear of retaliation.

Despite what some describe as a new cancel culture, often based upon controversial opinions posted on the internet, where that posting may cause a person to be the recipient of public outrage, others feel it is still important to speak your mind.

One prominent person wrote a book about it.

Why It’s OK to Speak Your Mind 1st Edition

“Political protests, debates on college campuses, and social media tirades make it seem like everyone is speaking their minds today. Surveys, however, reveal that many people increasingly feel like they’re walking on eggshells when communicating in public. Speaking your mind can risk relationships and professional opportunities. It can alienate friends and anger colleagues. Isn’t it smarter to just put your head down and keep quiet about controversial topics?

In this book, Hrishikesh Joshi offers a novel defense of speaking your mind. He explains that because we are social creatures, we never truly think alone. What we know depends on what our community knows. And by bringing our unique perspectives to bear upon public discourse, we enhance our collective ability to reach the truth on a variety of important matters.

Speaking your mind is also important for your own sake. It is essential for developing your own thinking. And it’s a core aspect of being intellectually courageous and independent. Joshi argues that such independence is a crucial part of a well-lived life.

The book draws from Aristotle, John Stuart Mill, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell, and a range of contemporary thinkers to argue that it’s OK to speak your mind.”

Sounds okay.

But, maybe not great.

Why? Many people are not buying into the whole speak your mind philosophy.

It appears less and less people are speaking their minds.

Do you speak you mind at work? With family on lunch or dinner gatherings? With friends in entertainment settings?

Check out this recent study.

New Study Shows People Have Never Been More Afraid to Speak Their Minds

Crucial Learning research finds those who make the harshest judgements of others are three times more fearful to speak up.

News provided by

Nov 09, 2021, 11:09 ET

PROVO, Utah, Nov. 9, 2021 /PRNewswire/ — A new study by Crucial Learning, a learning company with courses in communication, performance, and leadership, found that a shocking 9 out of 10 people have felt emotionally or physically unsafe to speak their mind more than once in the past 18 months. Unsurprisingly, the conversation topics that have generated the most fear include political or social issues (74 percent) and COVID-19 issues (70 percent).

The study of more than 1,300 people found that instead of voicing their opinions or concerns, respondents are resorting to a host of unhealthy behaviors that are crippling constructive dialogue and driving viewpoints farther apart. These behaviors include:

- Staying silent but feeling inauthentic (65 percent)

- Avoiding people (47 percent)

- Silently fume and stew (42 percent)

- Ruminating about all the things they’d say if they had the courage (39 percent)

- Faking agreement (19 percent)

- Severing relationships (14 percent)

Respondents shared colorful, real-life stories of situations in which they were afraid to speak their minds on these controversial subjects. A few examples:

- “My closest friends are convinced that anti-vaxxers are all ignorant fools who can’t understand science and are most likely evil white supremacists bent on destroying the world. When they get together in a group, they all make clever jokes about how awful these people are…[the] thought that if I speak up, they will think of me that way is horrible….So I’m a little frozen. I just sit quietly until the conversation moves on.”

- “Since COVID, my mother has surprised the family four times with the news that she’s rented an Airbnb for us. My dad has cancer and is supposed to follow guidelines for unvaccinated people. When we tell mom what we think, she calls everyone selfish and gets aggressive.”

Thirty-nine percent of survey respondents reported feeling unsafe either every day or every week. Only 7 percent report that they are just as confident as ever in social situations.

Emily Gregory, a co-researcher of the study and coauthor of the brand new third edition of Crucial Conversations, said the results begged the question: What is causing this heightened fear?

“Is the sole cause of our anxiety and subsequent silence the results of a volatile social landscape?” asked Gregory. “Or are there other factors at play and we’re actually in more control of our conversations and outcomes than we think?”

“For decades, our research has shown that when we’re talking about issues that are emotionally and politically risky, we tend to see the other person in a more negative light,” added Joseph Grenny, co-researcher and coauthor of Crucial Conversations. “We tell ourselves stories about our situation that turn us into virtuous victims and the other party into evil villains. This storytelling generates emotions of disgust and fear that we bring into the conversation. These emotions are responsible for provoking much of the conflict we experience as opposed to the toxicity of the topic itself.”

Leaning on a long-established concept in psychological research called the Least Preferred Coworker scale, Gregory and Grenny asked subjects to describe their level of fear in a recent social situation and their scaled perception of the person(s) they were fearful of addressing – for example, were they more open or close minded, informed or ignorant, or rational or irrational? Using stepwise regression, they next measured how much of their fear could be accounted for by more negative characterizations of others.

The result? Those who tended to tell more extreme stories about their conversational counterparts were more than three times more likely to feel fearful and 3.5 times more likely to lack confidence in speaking their minds.

“We were stunned to see the size of the effect stories have on our confidence and ability to speak up,” Gregory reports. “But it makes sense. If I tell myself you are an ignorant, evil, jerk, I’m more likely to think you’ll be vindictive—or worse—if I disagree with you.”

Having identified subjects who faced similar communication challenges, but generated more confidence and less fear, Grenny and Gregory asked them to identify skills that help speak up with poise and integrity. Top skills included:

- Make it safe (used by 76 percent of confident subjects). When emotions escalate, good crucial conversationalists reassure others of their respect for them and point out values they both share.

- “Last winter I yelled at a fellow snow shoeing partner as he told me the Dems are shutting down the freedom of speech of Conservatives. Then I calmed down and told him that he and I both wanted similar things in our country – safety, jobs, education, protected environment, etc. He tried to engage me on gun rights and I just listened and didn’t get excited. It calmed both of us down.”

- Get curious (used by 72 percent). Rather than try to decide “who is right,” they sincerely try to understand the world view of the other person. They ask questions, seek to understand, and show interest.

- “We discussed our opposing views on the renaming of our university based on racist associations of the current name. My friend saw me in a university T- shirt and came into the conversation hot. As we heard each other out we realized there was a lot we agreed on.”

- Start with facts, not judgments or opinions (used by 68 percent). Carefully lay out the facts behind their point of view. Use specific and observable descriptions.

- “We were talking about vaccine mandates. I felt confident sharing information that is not generally known from sources like the CDC website and others to explain my decision. I was calm, able to ask clarifying questions, and confident sharing my decision…”

- Don’t focus on convincing (used by 48 percent). Don’t let your main goal be to change the other person’s mind. Instead, encourage the sharing of ideas and listen before responding.

- “I’ve had numerous conversations recently about the prime minister in Canada. My husband believes he’s responsible for ruining the country. I felt confident holding the conversation because I can express my views without telling him he’s wrong or making him feel defensive. I ask him questions that encourage him to contemplate a different point of view without insisting that he’s wrong.”

- Be skeptical of your point of view (used by 42 percent). Conversations work best when you come in with a combination of confidence and humility. Be confident that you have a point of view that is worth expressing, but humble enough to accept that you don’t have a monopoly on truth and new information might modify your perspective.

- “My friend and I had a heated conversation about homelessness. We came from different perspectives of who the homeless are (are they lazy drug addicts, or victims of misfortune and mental illness, etc.?) Because we were both open to new information, we both came to a more nuanced view of things. Our conversation ended up at a better understanding.”

- Own your right to have your opinion (used by 11 percent). Rather than rely on others to validate your right to your opinion, take responsibility to validate yourself.

- “Our daughter and son-in-law have recently talked to my husband and me about two difficult topics: Covid vaccinations and white privilege. I was uncomfortable discussing it and at first tried to smooth it over, but then gained confidence and was comfortable talking about it. I recognized that my viewpoints and beliefs are not crazy or ignorant and that I have the right to make my own decisions and talk about why I made them. I resist the pressure to feel like my thoughts and decision are ‘less than.'”

About Crucial Learning

Formerly VitalSmarts, Crucial Learning improves the world by helping people improve themselves. We offer courses in communication, performance, and leadership, focusing on behaviors that have a disproportionate impact on outcomes, called crucial skills. Our award-winning courses and accompanying bestselling books include Crucial Conversations for Mastering Dialogue, Crucial Conversations for Accountability, Influencer, The Power of Habit, and Getting Things Done. CrucialLearning.com.

SOURCE Crucial Learning

Related Links

http://www.cruciallearning.com

~ ~ ~

OPENING PHOTO Femcompetitor.com, grapplingstars.com, fciwomenswrestling.com, fcielitecompetitor.com, fciwomenswrestling2.com Christina-Morillo-pexel.com-photo-credit

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedom_of_speech

https://www.fcielitecompetitor.com/

https://fciwomenswrestling.com/