fciwomenswrestling.com article, pixabay.com pexels.com photo credit

Even in the most profoundly successful life, and of course in those not so, misery truly does love company.

Loneliness not only loves company, it needs it.

In our exploration of one Independent and International film after another, one of the most effective and embracing films that speaks to the overwhelming fog of loneliness is the Turkish classic entitled Distant.

Or translated Uzak.

Uzak is a 2002 Turkish film directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan. It was released as Distant in North America, a literal translation of its title. The movie is the winner of 31 awards including Best Actor at Cannes, Special Jury Prize at Chicago, and Best Balkan Movie at Sophia International Film Festival.

Uzak tells the story of Yusuf (Mehmet Emin Toprak), a young factory worker who loses his job and travels to Istanbul to stay with his relative Mahmut (Muzaffer Özdemir) while looking for a job. Mahmut is a relatively wealthy and intellectual photographer, whereas Yusuf is almost illiterate, uneducated, and unsophisticated. The two do not get along well.

Yusuf assumes that he will easily find work as a sailor, but there are no jobs, and he has no sense of direction or energy.

Meanwhile, Mahmut, despite his wealth, is aimless too: his job, which consists of photographing tiles, is dull and inartistic, he can barely express emotions towards his ex-wife or his lover, and while he pretends to enjoy intellectual filmmakers like Andrei Tarkovsky, he switches channels to watch porn as soon as Yusuf leaves the room.

It was Mahmut who captivated this writer’s attention.

When you have so much to live for, yet already lost what you had been living for, the future life can become a lifeless dance of simply going through the motions of pretending to be alive but being fully aware that you are not.

And worse?

You have no desire to do anything about it and or change how truly empty it has become.

The other aspect to this film that caught me off guard were my previous perceptions of Turkish society and here are the cinematic reasons as to why.

As shared at the global news and information source telegraph.co.uk, “The most controversial incident in the colorful life of Lawrence of Arabia was made up by the celebrated hero, according to new forensic evidence.

The brutal sex attack on Lt Col T E Lawrence by Turkish soldiers, which allegedly took place while he was serving as the British liaison officer during the Arab revolt, was considered so contentious that it was covered up by the British Army.

But now, a new history of the Arab revolt is to claim that Lawrence invented the attack in order to smear political opponents and fulfill his own sado-masochistic urges.”

The powerful and impacting masterpiece Lawrence of Arabia played by Peter O’Toole, sure painted a very nasty picture of the Turks for me. I never forgot it.

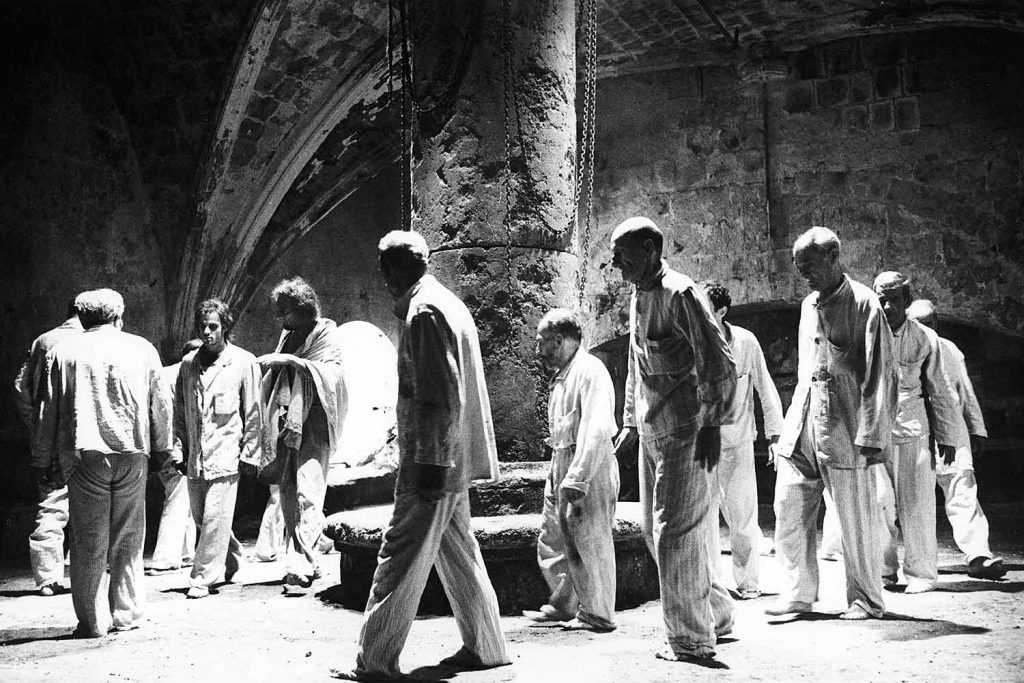

Enter Midnight Express.

The informative site imdb.com summarizes the film well. “Billy Hayes, an American college student, is caught smuggling drugs out of Turkey and thrown into prison.”

Midnight Express is a 1978 American-British-Turkish prison drama film directed by Alan Parker, produced by David Puttnam and starring Brad Davis, Irene Miracle, Bo Hopkins, Paolo Bonacelli, Paul L. Smith, Randy Quaid, Norbert Weisser, Peter Jeffrey and John Hurt.

It is based on Billy Hayes‘ 1977 non-fiction book Midnight Express and was adapted into the screenplay by Oliver Stone.

Hayes was a young American student sent to a Turkish prison for trying to smuggle hashish out of Turkey. The film deviates from the book’s accounts of the story – especially in its portrayal of Turks – and some have criticized this version, including Billy Hayes himself.

Later, both Stone and Hayes expressed their regret about how Turkish people were portrayed in the film.

It certainly had an effect on me.

Even if I had never seen the film and desired to visit Turkey, I would never bring drugs into any foreign country, but after watching Midnight Express there was no way I was ever going to visit Turkey for any reason.

What if the Turkish Inspectors just planted the drugs on me?

No one would ever see me again.

Regarding Turkey?

It gets worse.

Remember Gallipoli?

First let’s provide the background.

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign, the Battle of Gallipoli or the Battle of Çanakkale, was a campaign of the First World War that took place on the Gallipoli peninsula (Gelibolu in modern Turkey) in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916.

The peninsula forms the northern bank of the Dardanelles, a strait that provided a sea route to the Russian Empire, one of the Allied powers during the war. Intending to secure it, Russia’s allies Britain and France launched a naval attack followed by an amphibious landing on the peninsula, with the aim of capturing the Ottoman capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

The naval attack was repelled and after eight months’ fighting, with many casualties on both sides, the land campaign was abandoned and the invasion force was withdrawn to Egypt.

The campaign was one of the greatest Ottoman victories during the war. In Turkey, it is regarded as a defining moment in the nation’s history: a final surge in the defense of the motherland as the Ottoman Empire crumbled.

The struggle formed the basis for the Turkish War of Independence and the declaration of the Republic of Turkey eight years later under Mustafa Kemal (Kemal Atatürk), who first rose to prominence as a commander at Gallipoli.

The campaign is often considered as marking the birth of national consciousness in Australia and New Zealand and the date of the landing, 25 April, is known as “Anzac Day“, which is the most significant commemoration of military casualties and veterans in those two countries, surpassing Remembrance Day (Armistice Day).

Now for the film which contained some of the most hypnotic music in cinematic history.

Gallipoli is a 1981 Australian drama war film directed by Peter Weir and produced by Patricia Lovell and Robert Stigwood, starring Mel Gibson and Mark Lee, about several rural Western Australian young men who enlist in the Australian Army during the First World War.

They are sent to the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire (in modern-day Turkey), where they take part in the Gallipoli Campaign.

During the course of the movie, the young men slowly lose their innocence about the purpose of war. The climax of the movie occurs on the Anzac battlefield at Gallipoli and depicts the futile attack at the Battle of the Nek on 7 August 1915.

Gallipoli provides a faithful portrayal of life in Australia in the 1910s—reminiscent of Weir’s 1975 film Picnic at Hanging Rock set in 1900—and captures the ideals and character of the Australians who joined up to fight, as well as the conditions they endured on the battlefield.

The numerous running sequences in the film are set to Jean Michel Jarre‘s Oxygène.

It does, however, modify events for dramatic purposes and contains a number of significant historical inaccuracies.

Here we go again.

The Turks are not presented in the most positive way.

Thankfully the influential and brilliant Australian actor Russell Crowe did something about those inaccuracies.

As reported at irishtimes.com, “Russell Crowe’s new film The Water Diviner has been praised by the Australian embassy for its even handed portrayal of the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign.

The deputy head of mission in Dublin Paul McEachern told Crowe he had done more to promote bilateral relations between Australia and Turkey with his film than any diplomat has done.

The Water Diviner is the story of an Irish-Australian Joshua Connor who goes looking for the bodies of his three sons who he believes to have been killed at Gallipoli.

The film is noteworthy for its sympathetic portrayal of the Turkish experience of the war. At one stage when Crowe’s character says that 10,000 Australian and New Zealand troops (Anzacs) were killed at Gallipoli, the Turkish general responds that 70,000 Turks were killed in the campaign.”

In summation?

“Crowe has called for a reappraisal of the Gallipoli campaign from an Australian and New Zealand point of view. “You know because we did invade a sovereign nation that we’d never had an angry word with. And I think it’s time it should be said.”

Yes Mr. Crowe. Well said.

After watching Distant, in its deep and very quiet sad depiction of loneliness, I had a chance to view Turkish society from a very different perspective and felt both empathy and a desire to visit this hypnotic country for the first time that I could remember.

Also sad and symbolic, Uzak (Distant) was the last film that the actor Emin Toprak would be involved with, as he died in a car accident soon after filming was completed.

He was only 28 years old.

In modern times, loneliness invades all countries and continents.

Is there something that we can do about it?

Loving Yourself When You Feel Lonely

By Margaret Paul, Ph.D. Submitted On December 13, 2016

One of the saddest and most dysfunctional aspects of our current culture is that it fosters loneliness. It’s not hard to imagine that when most people lived in tribes or small villages, loneliness was not the epidemic that it currently is.

Loneliness is the feeling we have when we want to connect with someone and there is no one around to connect with, or the person or people who are there are closed and unavailable for connection. We can feel lonely when alone, and we can also feel lonely with others who are shut down and closed to connection.

We are social beings and we are hard-wired to long for connection and the sharing of love. Hopefully, understanding that loneliness is a natural core painful feeling coming from a primal need, will help you to remove any judgment from feeling lonely. Judging yourself for feeling lonely is the opposite of loving yourself. Judging yourself only serves to make you feel alone inside, and the combination of loneliness and aloneness leads to depression and despair. Loneliness is hard enough to manage without making it harder by judging yourself for it.

As an only child with disconnected parents, I was often very lonely. The loneliness was so big that I learned seemingly positive ways of avoiding feeling this feeling – reading, doing arts and crafts, being immersed in school and spending as much time as I could at friends’ houses. In fact, I did such a good job of avoiding this feeling that I was completely unaware that I was often very lonely.

It came as a shock to me when, one day, I felt a searing pain throughout my body. I asked my spiritual Guidance what this feeling was and she said, “This is loneliness.” “Wow!” I answered. “No wonder I’ve avoided it all this time!”

My Guidance suggested that I hang out with the feeling, welcome it, embrace it and stay open to learning about what it had to teach me. I hung out with it for two months and it taught me volumes. One of the things it taught me was how to love myself through the loneliness.

The first thing I learned to do was to become aware of the feeling, then name it and embrace it with compassion. My inner child feels seen, heard and loved when I name the feeling and compassionately embrace it. It’s easy to use various addictions and other forms of self-abandonment to avoid feeling lonely, but this isn’t loving to ourselves.

The next thing I learned to do is to open to learning from the feeling. If I feel lonely when I’m alone, it’s telling me that I need to reach out for connection. Sometimes being alone doesn’t feel lonely and other times it does. If it does, then loving myself means taking loving action for myself – such as calling a friend or family member. Loving yourself might mean that you need to make friends. Loving action might be looking into meetup.com, or taking a class with like-minded people, or joining a spiritual or religious organization or a 12-Step group, or some other activity where you might meet like-minded people. What is not loving is to judge yourself or avoid the feeling with some other form of self-abandonment.

If I feel lonely when I’m with another person, first I need to check in to make sure I’m open. If I’m not, then I need to do my Inner Bonding work to explore what I’m protecting again – what I’m trying to control or avoid. If I am open, then my loneliness is likely telling me that the person I’m with is closed to connection with me. Then I have the choice to love myself by opening to learning with them, or to lovingly disengage. If you are often lonely with your partner, loving yourself might mean seeking help with your relationship, even if your partner isn’t open to counseling or facilitation.

If I’m with a group, the feeling might be telling me that this group isn’t my tribe, or it might be telling me that I need to move around within the group to find the one or two people with whom I can connect.

There may be a lot of information you can gain from compassionately attending to your loneliness. Loving yourself through loneliness means embracing it, learning from it, and taking loving action on your own behalf.

Margaret Paul, Ph.D. is the best-selling author and co-author of eight books, including “Do I Have To Give Up Me To Be Loved By You?” and “Healing Your Aloneness.” She is the co-creator of the powerful Inner Bonding® healing process. Learn Inner Bonding now! Visit her web site for a FREE Inner Bonding course: http://www.innerbonding.com or email her at margaret@innerbonding.com. Phone sessions available.

~ ~ ~

http://ezinearticles.com/?Loving-Yourself-When-You-Feel-Lonely&id=9597219

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/expert/Margaret_Paul,_Ph.D./16527

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/9597219

http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2014/20-great-films-about-loneliness-that-are-worth-your-time/

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0077928/